On the 15th of March 44 AD, Julius Caesar was assassinated by a group of senators in the Roman senate. 23 stabs punctured Caesar and he died as he bled out onto the floor. Afterwards, Antistius examined the body to ascertain which of the wounds had delivered the fatal blow (it was a stab to the chest, which ruptured Caesar’s aorta).

This would later be known as the first recorded autopsy in history. And not only would this practice eventually become standard medicinal process, its spirit would be lifted beyond medicine, inspiring leaders of all walks to ask: “What blow made the kill?”

Post mortems (“after death”) are a process by which an outcome is dissected. Although initially designed to investigate failure, they can be applied to all kinds of result. The idea is understand the mechanisms of what went right and what went wrong in a project or event. Surfacing knowledge like this is a powerful method of learning from the past.

The limitation of the post mortem is, of course, its focus on the rear view mirror. That’s where premortems come in.

The power of imagination

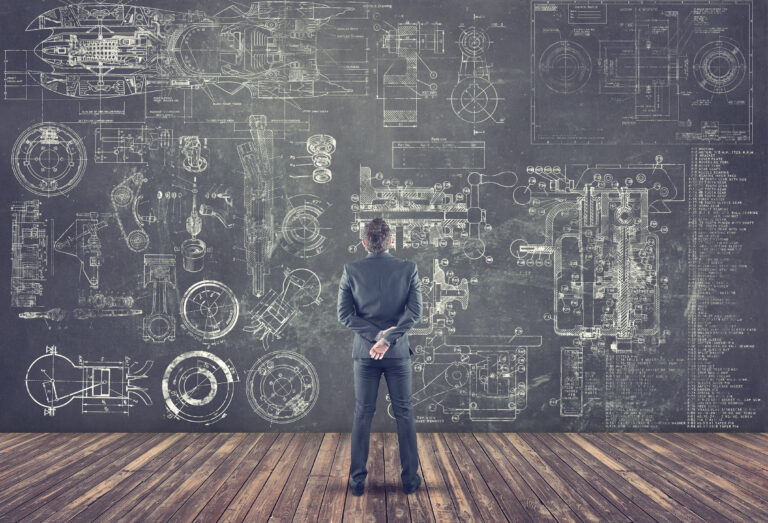

Psychologist and performance expert, Gary Klein, believed there might be a better process for thinking about and preparing for risk. Post-mortems, while useful, were too backwards looking to sufficiently mitigate future errors. And risk-planning exercises, while well intentioned, too often produced vague, abstract and non-actionable answers.

So, in 2007, Klein devised a new approach, which he called the premortem. In this process, instead of asking participants to envision future risks, participants are asked to imagine themselves in the future where the project has already failed.

As Klein explains in the Harvard Business Review:

A premortem is the hypothetical opposite of a postmortem. A postmortem in a medical setting allows health professionals and the family to learn what caused a patient’s death. Everyone benefits except, of course, the patient. A premortem in a business setting comes at the beginning of a project rather than the end, so that the project can be improved rather than autopsied. Unlike a typical critiquing session, in which project team members are asked what might go wrong, the premortem operates on the assumption that the “patient” has died, and so asks what did go wrong. The team members’ task is to generate plausible reasons for the project’s failure.

Klein’s research has shown that when participants use premortems – vs. traditional risk exercises – they are able to better engage the power of their imaginations. This reliably produces more creative, tangible, specific – and therefore – actionable ideas.

How to Premordem

Let’s say you have a big goal for 2021. How might you, as an individual, conduct a premortem? Below are steps you might take (for a group exercise try this).

Step one: Prepare for the session

Block off a time and space when and where you can premortem without distraction. For the session to be successful, you need enough quiet to let your mind wander. You’ll want anywhere from 30 minutes to 2 hours.

Pick one goal that you care about. Then assemble some pens, sticky notes and a large piece of paper or whiteboard. On the large piece of paper, draw these columns:

- Paths to failure

- Must have/required

- Must avoid/eliminate

- To do

It’s worth mentioning that you want a calm and expansive state of mind for this kind of work. While a premortem is ultimately about risk, you do not actually want to be in a state of anxiety or fear when entering this process – the body’s fight, flight or freeze modes are not conductive to creative thinking.

Step two: imagine spectacular failure

On the day of the exercise, sit down and picture yourself in the future. The project or goal has been abysmally disappointing. Try to sense yourself in that moment – taste, see, hear, and feel what that’s like.

Now, ask yourself:

- “What happened?”

- “What was “lacking” that contributed to the result?”

- “What was “present” that contributed to the result?”

- “Where did you ignore important signals and red flags?”

- “Which of your emotional habits led to the result?”

- “How was this like previous mistakes?”

- “How was this totally unlike previous mistakes?”

As insights come to you, use your pen and the sticky notes to jot them down.

Step three: Categorize the insights

Once you’ve spent some time – say 10 – 20 minutes – envisioning the failure and making notes, it’s time to categorize the insights. Move all of your plausible reasons to the “paths to failure” column.

Now, take and step back, and ask yourself the following two questions:

“What is absolutely critical or required for this project to succeed?”

And

“What is absolutely critical to avoid or eliminate to prevent these risks?”

Fill up more sticky notes with answers. Place them under the column.

Step four: Formulate an action plan

Finally, ask yourself:

“What actions do I need to take to safeguard against what I’ve just imagined and brainstormed?”

Determine the actions you will take, writing them down either on more sticky notes or in a document you can keep for your planning purposes.

Et voila! You are done. Your individual goal premortem.